The 40 year old logging virgin

Whatever brought you here, it’s possible you think of logging as entirely un-sexy. Let me challenge that thought: if UI is how apps talk to end users, logging is how programs talk to devs.

This often overlooked line of communication may be the difference between a fling and a happy long term relationship with your production code.

I have a confession to make

Despite being a 40 year-old accomplished developer, I’ve never done proper logging. I mean yes I have used a debugger output window, but that’s hardly going beyond 1st base according to this famous table I just made up:

| Base | Logging capability |

|---|---|

| First base | Console |

| Second base | Console + debugger output |

| Third base | Console + output + rolling file |

| Home run | Hosted centralized queryable logs |

It’s not that I’ve actively avoided it, it’s just a combination of circumstances that led me to where I am now, sometimes I was working on prototypes before handing them to real developers, other times with solutions so large that logging was handled elsewhere or by someone else.

From logging zero to logging hero 🦸♂️

Whatever the reason, today I have this project that I lone-wolf, and it’s in dire need of logging. It processes an incoming stream of data and generates thousands of API calls.

When these calls return unexpected results, I open a ticket, which often turns into someone asking me for some useless piece of additional information, seemingly to delay having to do any work.

It was clear that there was only one way out of this hell hole, I needed to log their own API activity so that they could peruse it at their leisure. Sigh.

Poor man won’t help you

I try not to trivialize things that I’m not familiar with, but I have to admit I’ve often trivialized logging, thinking how hard can it possibly be? While not necessarily hard, turns out logging isn’t just a glorified console print either.

At the beginning I went for a poor man’s logging kind of approach, which is my favorite approach to all problems that I trivialize. I thought to myself that my code already does a decent amount of tracing, I could simply “redirect” it to some ELK stack and be done with it. How naïve of me.

Logging done right

I understand how ridiculous it is for me to devsplain this after having done it only once, but let’s be honest: this is what you’re here for, otherwise you’d be reading a book, not a blog.

I’ve boiled the requirements for a log to be useful down to just two:

- Events can easily be grouped by type

- Event properties are informative and easily queryable

The second requirement is just a matter of picking the appropriate logging framework and the right event repository, which we’ll get into later.

The first requirement however is the one that made me drop my Trace redirecting idea, because it would’ve required me to give all events an event type id, which is very unappealing to me. I don’t want to maintain an event type list somewhere that needs attention whenever I log something new. I hate this kind of housekeeping.

Enter Serilog

If you go to Serilog’s site they advertise their “powerful” structured logging as a major differentiator. Their structured logging mechanism relies on message templates that are basically a more elaborate version of .NET’s String.Format:

// this creates a log event of level "Debug"

logger.Debug(

// this is the message template

"{RequestMethod} {RequestPath} returned status \

{StatusCode} {Status} in {Elapsed} ms",

// the values referenced in the message template above

response.RequestMessage.Method.Method,

requestPath,

int response.StatusCode,

response.StatusCode,

elapsedMs)

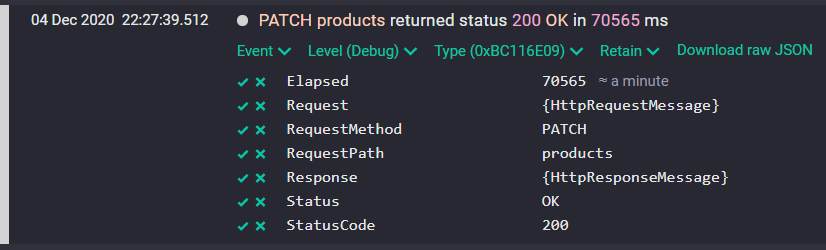

This code creates the following log entry:

PATCH products returned status 200 OK in 2534 ms

└► {

RequestMethod: "PATCH"

RequestPath: "products"

StatusCode: 200

Status: "OK"

Elapsed: 2534

}

This is fanciful enough, but so far nothing has been done about my first requirement of useful logs, the ability to group them by type.

Implicit event types 👍

Message templates are very useful to define a log entry that is both meaningful and readable, but these templates can also be used as an event type, because all events that have the same message template are also events of the same type.

Obviously, you don’t necessarily want to be storing "{RequestMethod} {RequestPath} returned status {StatusCode} {Status} in {Elapsed} ms" but hashed to 0xBC116E09 and it looks a lot more like a natural identifier. Serilog’s RenderedCompactJsonFormatter automatically adds this hash to the rendered json, and so does Seq which I’ll get to later.

These implicit event types are perfect for my needs. With both my requirements fulfilled, it’s time to do the deed.

Warning: may contain traces of F# 🥜

In order to create text file logger, according to Serilog’s doc you may start with something like this:

// this logger writes to a rolling file

// NOTE: be careful with 'use' bindings, they may dispose of

// the logger earlier than you anticipate

use logger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

.WriteTo

.File("log.txt", rollingInterval = RollingInterval.Day)

// override default level to see 'debug' and 'verbose' events

.MinimumLevel.Verbose()

.CreateLogger()

// assign this logger as the main static logger

Serilog.Log.Logger <- logger

// test the new logger

logger.Information "I did a log!"

This is a proper 3rd base logger according to the table above, and while this works, there’s still a few surprises ahead.

My first issue with this approach is that I still have lots of tracing in my code that I don’t want to miss, and I also don’t want to convert to Serilog calls. In fact, some trace messages were being generated by referenced projects beyond my responsibility. Thankfully, Serilog has a sink for that:

// this listener enables logging of trace events

use serilogListener =

// instanciate a new listener

new SerilogTraceListener.SerilogTraceListener("Trace",

Filter = EventTypeFilter SourceLevels.Verbose)

// remove all Trace listeners and add Serilog's

// ⚠ does not sem to work in FSI ⚠

Trace.Listeners.Clear ()

Trace.Listeners.Add serilogListener |> ignore

Trace.verbose "Trace routed to main logger"

The eagle eyed reader may have realized that Trace.verbose doesn’t exist, if your interested, its one-liner definition is here. Anyway so far so good, We can both create informative log entries with and also collect all legacy Trace messages. This is going great!

Or is it?

One issue with the logger we just created is that it collects all logs in a text file, but we have to open it to see things happening in real time. This is a step back from the debugger output window. If only we could get our logs to appear in the output window at the same time. Wait, there’s a sink for that too! Enter Serilog.Sinks.Debug!

// this logger writes all events to output

use outputLogger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

.WriteTo.Debug()

.MinimumLevel.Verbose()

.CreateLogger()

To have all events from the main logger redirected to the one above, we add this line to its declaration:

// add this line to chain loggers

use logger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

// ...

.WriteTo.Logger(outputLogger) // ← new

.CreateLogger()

Stack overflow, not the website, the Ꞙ***🤬 exception

Run the code above and you’ll be hit with a stack overflow exception with zero stack trace. Your code just goes 💥 boom 💥 soon after launch, without any information. If you’ve created a lot of code before running it, trust me this may cost you a night of sleep. Thankfully this 40 year-old former logging virgin is here to tell you what happened.

That escalated quickly 😱

The problem is that Serilog’s output logger writes using Debugger.Write which also writes to the trace, and since we were capturing the trace to log it, we created an infinite logging loop of doom. The solution is to create our own debug sink, which is trivial when you consider that the only line that matters in the code below is the last one:

/// This debug sink writes to output window without generating trace events

type NoTraceDebugSink () =

// default message template

let defaultDebugOutputTemplate =

"[{Timestamp:HH:mm:ss} {Level:u3}] {Message:lj}{NewLine}{Exception}"

let formatter =

MessageTemplateTextFormatter(defaultDebugOutputTemplate, null)

interface ILogEventSink with

member _.Emit logEvent =

use buffer = new StringWriter()

formatter.Format(logEvent, buffer)

// Debugger.WriteLine (string buffer) // ← this also writes to trace!

Debugger.Log (0, null, string buffer) // ← this does the trick 👍

The code above is super boilerplaty, only the last line matters, but now we can use this sink to create a new logger:

// replace stock sink with the one above

use outputLogger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

.WriteTo.Sink<NoTraceDebugSink>() // ← new

.MinimumLevel.Verbose()

.CreateLogger()

Farewell stack overflow, you shall not be missed.

The next logical step

When my existing process runs in interactive mode, it displays a whole bunch of stuff in the terminal so my colleagues think that I’m super busy and smart. I quickly realized that a lot of what I displayed in the terminal is duplicating some of my log events.

The next logical step is to drop most of this console output code, and instead let some events appear in the console as execution happens. Thankfully (say it with me) there’s a sink for that! It’s called Serilog.Sinks.Console so let’s instanciate it and daisy chain it:

// this logger writes information-level events to the console

use consoleLogger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

.WriteTo.Console()

.Filter.ByIncludingOnly(fun e -> e.Level = LogEventLevel.Information)

.CreateLogger()

// chain it to the main logger

use logger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

// ...

.WriteTo.Logger(consoleLogger) // ← new

.CreateLogger()

Now notifications about process milestones are sent to the console as well as logged to any configured sink with the same line:

Serilog.Log.Information "Something important"

Events that were just sent to the terminal now can be seen in any of your configured sinks, which is useful to diagnose code that you’re not running in interactive mode such as ongoing scheduled production processes.

You can connect to your event sink of choice halfway through a running session and you’ll see whatever would be displayed in the terminal as if you had executed it manually! 🎉

Time to score that home run

It’s been a long journey, but thanks to it, between 3rd base and the home plate there’s only a single line of code. We need a hosted centralized log repository, so we need to move away from the rolling file. I’m going to use Serilog.Sinks.Seq here but since this choice only impacts one line of code, feel free to do your own research and try different solutions. Note that you can install the free dev version of Seq on the smallest linux box in Azure, it seems to work fine.

// replace the rolling file with Seq

use logger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

.WriteTo

//.File("log.txt", rollingInterval = RollingInterval.Day) ← old

.Seq("http://your.seq.host", apiKey = "y0ur4p1k3y==") // ← new

// same as before:

.WriteTo.Logger(outputLogger)

.WriteTo.Logger(consoleLogger)

.CreateLogger()

That’s it! Our logs now appear in Seq almost in real time!

You can click on any event to see the details. Event properties that aren’t scalar (such as strings or numbers) can be expanded to see their properties to any depth as far as I can tell.

{HttpRequestMessage} and {HttpResponseMessage} abbreviated for… brevity

If the eagle eyed reader is still with us, they may have noticed these Request and Response properties that aren’t anywhere in the message template. You can add properties to events without polluting the message template by using ForContext, this is important so event lines remain concise.

logger

.ForContext("Request", response.RequestMessage, true)

.ForContext("Response", response, true)

.Debug(...) // same as above

The last boolean parameter indicates that the object should be destructured instead of displayed with .ToString().

One doesn’t just log an object

HttpRequestMessage and HttpResponseMessage are not good candidates to be used as-is. They have too many properties, none of which contain the request’s raw content that is the main thing someone needs to replicated it. But the worst part is that the response also contains the request in one of its properties!

The best thing to do here is to take the last step in our journey, and customize how certain objects are destructured which we’ll do with an extension method:

[<Extension>]

type LoggingExtensions =

[<Extension>]

static member ConfigDestructuring(config:Serilog.LoggerConfiguration) =

config

// this does not work in FSI

.Destructure.ByTransforming<HttpRequestMessage>(

// actual useful code, part 1

fun r ->

{|

FullUri = r.RequestUri

Raw = getRawContent r

|} |> box)

.Destructure.ByTransforming<HttpResponseMessage>(

// actual useful code, part 2

fun r ->

{|

Raw = r.Content.ReadAsStringAsync().Result // doesn't handle null content!

Headers = getResponseHeaders r

TrailingHeaders = r.TrailingHeaders

StatusCode = int r.StatusCode

Message = r.ReasonPhrase

|} |> box)

As you can see customizing how http messages are destructured simply consists of providing a function that returns any object, here we define it as an anonymous record with just the properties we need. Our new logic can be added to the main logger with the following line:

// add our own custom destructuring logic

use logger =

Serilog.LoggerConfiguration()

.WriteTo

.Seq("http://your.seq.host", apiKey = "y0ur4p1k3y==")

.ConfigDestructuring() // ← new

// ...

.CreateLogger()

With this change, HTTP messages are way more readable when added as properties of a log event, and they also don’t contain any authentication headers. Using this simple method you can override how any object is logged which allows you to log complex objects in ways that are far more readable or useful!

You have reached your destination 🏁

This may seem like a lot of code just for logging at first, but consider the following:

- it’s only a lot compared to the tiniest of solutions

- it’s all the code you’ll need even as your solution grows larger

- not all of it is necessary as some people won’t need trace while others won’t need console output

Moreover, this is all setup code that’s very easy to follow and to maintain. You’ll write it once and rip the benefits forever without almost never touching it again.

A word about monkeys 🐒

When someone asks you for additional information just to delay dealing with something, it’s called putting a monkey on your back, and if left unchecked you may wind up with an entire barrel of them.

In case you’re wondering, a barrel is the appropriate term for a group of monkeys. I’ll never cease to wonder at English’s super specific names for groups of different animal types. If you too wonder at this useless piece of trivia, or at any other part of this article, bless your heart, and please let me know on Twitter, and while you’re there you can also follow me, and/or retweet this article’s tweet, both of which I’d be eternally grateful for. In any event, merry Xmas to you and your family, and may 2021 be nothing like 2020.